The Tool Box needs your help

to remain available.

Your contribution can help change lives.

Donate now.

Sixteen training modules

for teaching core skills.

Learn more.

| Learn about the Strategic Prevention Framework model for preventing substance use and addressing other community issues. |

Nearly every community – large or small, urban, suburban, or rural – must cope, to some extent, with the use and abuse of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. Most communities try to combat this problem, and some are reasonably successful. Others find themselves doing everything they can think of, and barely staying even, or – worse – losing ground.

The difference is sometimes in the way they approach the problem.Those that are most successful often try to prevent the problem from starting. They focus on the community as a whole, and try to devise ways to help the community members who are most at risk – typically youth – to avoid the behaviors or situations that would put them in harm’s way. Although they don’t ignore law enforcement, medical treatment, policy decisions, public education, or other actions necessary to address the problem as it already exists, these successful communities try to reduce substance use permanently by taking a long-term perspective.

Most of the models we’ve described in this chapter look to both the present – addressing a current issue – and the future. In this section, we examine another that does the same – the Strategic Prevention Framework developed by CSAP, the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, part of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF) outlines a process that an organization, initiative, community, or state can follow in order to prevent and reduce the use and abuse of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs.

This framework can also be applied to other community issues, such as violence, health-related problems (obesity, heart health, diabetes, HIV), homelessness, or racial tensions and discrimination. By the same token, while SPF focuses primarily on youth, there is no reason that the model can’t be adapted to any population group.

The framework addresses both risk and protective factors. Risk factors are those elements within an individual or her environment that make her more susceptible to particular negative behaviors or conditions. Protective factors are the opposite – those elements within an individual or his environment that make him less susceptible to those negative behaviors or conditions.

Risk and protective factors vary, depending on the issues they relate to. Some examples of risk factors for alcohol abuse, for instance, include:

Acceptance of alcohol use and abuse may include such elements as the acceptance of binge drinking on weekends as a “stress reliever;” parties where large quantities of alcohol is consumed as a norm; and alcohol availability at public events – festivals, concerts, etc. This kind of tolerance is not confined to low-income or working-class communities. In many upper-class communities, at least until 20 or so years ago, large amounts of alcohol were consumed at dinners, weddings, etc., with the assumption that guests – many of them underage, and most at least slightly drunk – would then drive themselves home.

Some examples of protective factors for the same behavior:

The Strategic Protection Framework addresses risk and protective factors with a five-phase process. We’ll list the phases here, and discuss them in more detail later, in the “How-to” part of the section.

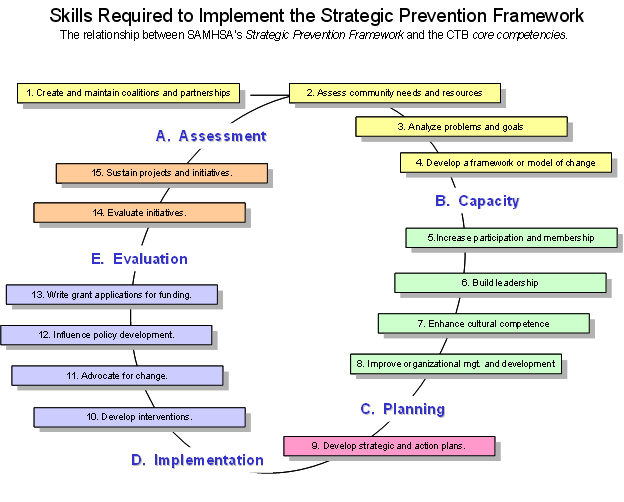

The Community Tool Box has hundreds of how-to sections that can be used to help implement the Strategic Prevention Framework in your community. The above Strategic Prevention Framework diagram is overlaid with the core competencies for community health and development found in the Community Tool Box. The following links will take you to Community Tool Box Toolkits and how-to sections for these CTB/SPF related core competencies.

Given that there are a large number of models available, what are the advantages of using SPF?

There is a fine line between prevention of a negative condition (e.g., substance use) and promotion of a positive one (e.g., a healthy lifestyle.) A well-run prevention program that focuses on eliminating risk factors and strengthening protective factors can turn into a promotion program that encourages citizens to take positive steps to make their lives as healthy and fulfilling as possible.

SAMHSA/CSAP awards grants to states under the SIG (State Initiative Grant) program; to community coalitions under the Drug Free Communities Support Program; and to community organizations to prevent the spread of methamphetamine use. In addition, SAMHSA awards grants to a variety of organizations, institutions, and agencies for the prevention and treatment of substance use for those with HIV/AIDS. While the total amount of these grants is relatively large, the number of recipients is still quite small, and most are large organizations and institutions. States may distribute their SIG’s to smaller organizations in communities, but the amount of money available is still relatively modest, and not all states have these grants.

These disadvantages largely apply to those who seek CSAP grants to implement SPF, either through state funds, or directly from CSAP. For those who simply want to use the framework, CSAP does provide access to a large amount of information, and can make it possible to put together an effective prevention program using local resources. In that case, having to contend with the potential problems raised by points 2 and 3 is not an issue.

Prevention, in the ideal, means just that. The best time to start a prevention program is before there’s a serious problem. In fact, with its emphasis on risk and protective factors, particularly for youth, the framework could act as prevention for nearly any undesirable issue, as well as promotion of healthy behaviors and environments. In that respect, it’s similar to asset development.

The reality in most communities, however, is that given the problems that already exist, most issues don’t get addressed until they reach crisis proportions, or at least become cemented in the public consciousness. Thus, the best time to embark on a strategic prevention initiative may be when the community is ready to turn its attention in that direction.

You can often hurry this process along by assessing where the community is at, and beginning a campaign to raise that readiness to the next step, or whatever step is necessary for the community to get on board with a prevention plan. The first part of a prevention initiative may in fact be an effort to increase community readiness. You may not begin to devise and implement a prevention program for a while, but the readiness development is all part of the same effort.

As with many of the “Who. ” questions in the Community Tool Box, this one not only has more than one answer, but is, in reality, more than one question.

CSAP awards several kinds of grants that focus on or include prevention, as mentioned earlier:

The first answer, then, is that SPF should be implemented by those who administer these grants at the state and local levels. They might be state and local health and human service officials, coalition coordinators, human service providers, universities, hospital and clinic administrators, etc. But, because of the nature of the grants, these folks are only the beginning. They are required to involve all stakeholders from the beginning, and that implies a much broader range of people.

If you take a community perspective on prevention, then stakeholders comprise all sectors of the community, and should be represented in planning, implementing, and evaluating the framework. These include:

All or most of these groups would probably be part of the Epidemiological Working Group mandated under the various grants, but should also be part of any SPF effort. As stated constantly in the Community Tool Box, we believe that, in most cases, participatory planning and implementation of programs leads to efforts that both meet real community needs and assure community support.

In addition, there are those who might run SPF programs that aren’t funded by CSAP, but that simply use the framework to structure their work. They are likely to be community-based health or human service organizations, community coalitions, local health departments, or similar groups that engage in prevention efforts either to respond to community needs or as part of a larger local initiative.

A typical universal program might involve community education efforts through the media, schools, and organizations. It might try to explain the effects of alcohol and various other drugs, conduct prevention classes in middle or elementary school, identify risk and protective factors, let people know where they can get more information, and generally raise community consciousness and concern about the issue. It might be aimed at a neighborhood, at the community as a whole, or even at a whole county or state. Who would be served in this case would be everyone the program could reach, in the hope of establishing community norms that work toward prevention, and alerting the community to existing risk factors.

Populations at risk that might be the subjects of a selective program vary from one community to another. Some of the most common:

This is not to imply that all adolescents who use alcohol or drugs will become abusers. In the U.S., large numbers of adolescents drink – often to excess – and somewhat smaller, but still significant, numbers smoke marijuana. Only a small percentage of these become dependent on these or other substances. That doesn’t change the number of non-dependent teens killed or injured in alcohol- and drug-related motor vehicle or other accidents, or the amount of emotional and property damage they may cause or suffer while under the influence. If all a prevention program does is to convince kids to think for a second before they act, it will have performed an enormous community service.

Indicated programs focus not on probabilities (populations likely to be at risk, for example), but on specific individuals who are known to be already involved in substance use. Depending on the program, these individuals could be identified and referred by school personnel, parents, the court system, law enforcement, social workers, therapists, or others who have contact with them. In such cases, it would be not only the participants, but those who referred them who are the users of SPF.

As described above, the SPF has five phases. We’ll examine those in more detail here to see how they guide the use of the framework.

SAMHSA/CSAP provides information, instruction, and technical support. There you can find a template for planning your effort; information on such topics as risk and protective factors; and links taking you to lists and descriptions of evidence-based programs and to numerous other helpful sites, including the Community Tool Box.

Phase 1: Assessment. In the assessment phase, you determine community needs and resources, and identify existing risk and protective factors.

One of the ironies of a prevention effort is that those most affected and damaged by the issue – substance users and abusers – are those least likely to want to be involved. Perhaps the best way around this, in addition to recruiting workgroup members from the population(s) most at risk, is to include those recovering from alcohol and drug dependency. They understand the substance use culture from the inside, while being clear on the need to prevent people from joining that culture.

In general, some of the questions you might try to answer through a community assessment include:

A community assessment of substance use can be conducted using some or all of a number of methods. In general, the more methods of collecting information you use, the better picture you’ll get of the issue in your community. Some basic ways of finding out about community needs and resources:

Understanding where the community is and starting from there is incredibly important. People simply won’t do what they’re not ready to. Until community members are aware of the problem and believe it is important, it’s unlikely that you’ll get much of the support needed for a successful prevention effort. Your first tasks in that case may be to get the community to that point, and to involve it in planning. Once community members understand the concept of prevention and see the need for it locally, it’s more than likely they’ll support and participate in your effort.

Tools that identify the dimensions and levels of community readiness have been developed. An instrument for determining community readiness that can be easily applied and scored by community members can be found in Community Readiness, and related Community Tool Box sections that support improving readiness.

Phase 2: Capacity.

Not only does the community have to be ready to take on a prevention effort, but it has to have the capacity to do so. This includes awareness and knowledge of community substance use and abuse; an understanding of how to create, implement, and maintain a prevention program; other community resources that can serve (are serving) to address the issue; widespread community support and participation; and the will to sustain the effort for the long term.

This doesn’t mean that everyone in the community has to understand, support, and be willing to participate in a prevention program, although this may be an ideal. Rather, it implies that there has to be a critical mass of support and knowledge in order to run an effective program.

To build community capacity:

If the community is already well aware of the problem – you may be able to concentrate on gathering support and volunteers to start planning your program. You may want to form a community advisory board or similar group to represent the effort.

Seek out individuals for either their skills or their enthusiasm, and ask them to do things they’re good at and/or find interesting. You may be able to find volunteers who are experienced in curriculum development, public relations, youth work, filmmaking, and other areas that might benefit the effort. People whose only apparent skill is a willingness to help can network, provide logistical support (stuffing envelopes, scheduling meetings, making phone calls), and help to recruit still others, as well as developing leadership capacity over the long term.

Phase 3: Planning.

The planning phase is at least as important as any other for two reasons: first, it plays out the participatory nature of the effort, thereby gaining both a variety of thinking and community buy-in, if it’s done well; and second, it creates the structure, organization, and content of the actual prevention program, by which that program will rise or fall. As a result, it’s important to go about planning carefully. More time spent on this phase can mean less trouble and greater success over the long run.

Some organizations place risk factors for adolescent substance use (and other undesirable behaviors as well) in four categories: community, family, school, and individual/peer. CSAP (see Tool # 2) adds a societal domain to these four, encompassing the roles of the national media, the Internet, and the wider culture in forming community and adolescent attitudes and behavior.

Protective factors for CTC reside in individual characteristics, in bonding (with family, particularly, but also with mentors and other significant adults), and in the healthy beliefs and clear standards imposed on adolescents by families and the community.

Developmental assets (similar to protective factors) for children and adolescents can also be divided into external and internal.

External assets are further divided into four categories:

Internal assets are also divided into four categories:

The goal here is to understand how these factors operate in your community – which are important and which less so, which are most likely to influence substance use among populations at risk.

Trying to limit the availability of drugs, for instance, is not just a matter of changing enforcement and/or attitudes in your community. Drugs may be equally available in the next community or neighborhood, or through sources other than those you crack down on. Furthermore, the new sources may be more dangerous to users than the old, both in terms of the drugs they offer and in their potential for violence. You might be able to rid your own neighborhood or community of drugs, but that doesn’t mean you’ve eliminated, or even reduced, their availability.

Programs you find may also take different forms. We’ve already discussed universal (aimed at the whole community), selective (aimed at a particular at-risk population), and indicated (aimed at identified at-risk or substance-involved individuals) programs. Another way to look at programs is as either individual or environmental.

Individual programs are aimed at helping individuals to develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills they need to change their undesirable behavior, or to maintain healthy behaviors. Some examples here might be school courses on the chemical and biological effects of alcohol and/or various drugs; parenting programs; smoking cessation groups; and various 12-step and similar programs.

Environmental programs seek to alter the environment to make it easier for people to change or maintain their behavior. These might include policy change (particularly as it relates to regulation of substances and enforcement of laws and regulations regarding substance use and abuse); media and other efforts to educate the community about the dangers of substance use (Surgeon General’s warnings on cigarette packs, anti-drunk-driving campaigns); and attempts to change community attitudes and norms.

Effective prevention strategies often include both individual and environmental elements.

CSAP encourages communities to find programs that work specifically for them. At the same time, for programs it funds directly or indirectly, it requires that, once they choose an evidence-based model to implement, they copy that model exactly. There are obvious reasons for this: once a model has been proven to work, it makes a certain amount of sense to try to reproduce it perfectly, since any change in it might affect its success. If the program you’ve chosen speaks directly to your community and your population, there is no real reason not to implement it just as its creators did.

In some cases, however – because communities and populations often differ in subtle and not-so-subtle ways – even the program that comes closest to addressing your situation may have elements that are unlikely to work in your community, or lack elements that would improve its effectiveness. In these cases, it’s important to acknowledge your experience and understanding of the community and its history.

If you’re funded by CSAP, you might try to negotiate appropriate changes in the implementation of the evidence-based model you’ve selected. If you’re not funded by CSAP, but are simply using SPF as a framework for a community prevention program, you can make your own adjustments as you plan your program. You can borrow some strategies from another evidence-based program that you’ve examined, for example, or devise some strategies of your own to add on to the program you’ve chosen.

It makes sense to start with an evidence-based program. Reinventing the wheel is unnecessary, especially if you already know that the wheel works quite well. Improving the wheel is not impossible, however, and if you have the opportunity and the ideas to do so, you might come up with a prevention program that works faster or more smoothly, and that avoids the particular potholes presented by the peculiarities of your community.

Your plan should be detailed enough that it could still be followed even if everyone involved in the planning suddenly decided to retire to a tropical island and left no forwarding address.

Phase 4: Implementation.

Now it’s time to put your prevention program into practice. This phase isn’t easy, but it will be a lot easier if you’ve done a good job planning and have the support of the community. Paying attention at the beginning of and throughout the implementation phase to some specific aspects of it will also make the task easier.

The same is true for the methods, content, and structure of the program itself. You’ve chosen an evidence-based model because it has proven itself and because it seems to fit your community, your population, and the issues they’re dealing with. It makes sense to stay as close to the model as possible, at least for an initial period, to see if it works as well for you as it did for others that tried it.

Phase 5: Evaluation.

Only by monitoring and evaluating your effort can you tell just how successful it is, and know what parts of it you need to change or strengthen. Evaluation should be ongoing throughout the life of the prevention program, and should cover at least three areas:

The results of your evaluation should be reassessed on a regular basis (typically once a year), and used to adjust your program to respond to changing community needs or to change or improve areas of it that aren’t working as well as they could. That’s the whole point of evaluation – to make your program better. Finding ways to make the effort stronger isn’t an admission of failure, but rather a way of keeping your work dynamic. No program is perfect – there are always some actions you can take to improve it. Programs that never change generally go downhill over the long run: change revitalizes staff and participants, and leaves room for experimentation that leads to new discoveries.

When you make major changes, tell the community about them, and ask for help if you need it. Adjustments may require more volunteers, more funding, a different method of reaching people, or some other change that the community can assist with. The opportunity to provide real aid leads to community ownership and support of the program.

The Community Tool Box considers evaluation such a valuable part of any intervention or initiative that it devotes four chapters – 36 through 39 – to it. You can find information about almost any aspect of evaluation in the more than 30 sections that comprise these chapters.

SAMHSA/CSAP doesn’t include a sixth phase of the prevention process, but we’ll suggest one here. It will be familiar to regular users of the Tool Box: keep at it indefinitely. You’re actually attempting to create long-term social change, and that takes time. You may see the changes you desire, but that doesn’t mean they’re permanent, or part of the community culture. or that they’ll remain part of that culture without being nurtured. Changes have to be maintained, and that means continuing at least some of the major elements of your prevention program for as long as substance use remains a problem in society.

CSAP’s Strategic Prevention Framework is intended as a structure for substance use prevention programs, although, because of its generality, it could easily be used for other prevention programs as well. The components of its process – assessment, capacity building, planning, implementation, and evaluation – are similar to those of the other logic models and frameworks described in this chapter.

The Strategic Prevention Framework, like several of the Other Models for Promoting Community Health and Development. focuses on risk and protective factors. Risk factors are those elements in the individual, family, peer group, or society that make it easier or more likely for someone to fall into substance use. Protective factors, on the other hand, are those elements in the individual or his environment that make it easier or more likely for him to avoid substance use.The assumption is that if you can reduce or weaken risk factors and strengthen protective factors in a population or community, its members are less likely to experience substance use problems.

CSAP provides funding for prevention both through states and directly to organizations. More important for the majority of prevention programs not funded by CSAP grants, the agency also provides web-based tools and information to help with each phase of development and implementation. CSAP’s website also provides links to evidence-based programs that can be used in the implementation phase with at least some degree of confidence that they’ll work.

Contributor Phil RabinowitzOnline Resources

Chapter 12: Prevention and Promotion in the "Introduction to Community Psychology" describes historical perspectives on prevention and promotion, the different types of prevention, examples of risk and protective factors, and various aspects of prevention programs and evaluation.

CSAP’s Western Center for the Application of Prevention Technologies. A step-by-step how-to on developing and implementing a prevention program.

Day for Prevention Video 1 - Community Partnerships and Coalition Building. This features a coalition that includes youth in decision-making – critical for an initiative meant to benefit youth.

Michigan’s Approach to A Strategic Prevention Framework, from the Michigan Department of Community Health. This is useful information outside the state of Michigan as well.

NIDA, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, part of the National Institutes of Health.

The Prevention Platform from SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration)/CSAP’s (Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, a subsidiary of SAMHSA). Technical assistance, funding information, valuable links, tools, etc. The all-purpose build-your-own-prevention-program website. Extremely valuable information.